Anatomy of the Digestive System

So today we're going to be taking a look at the digestive system. And one of the main reasons we're going to do this is because every single person has had a digestive system dysfunction throughout their lives, whether it's a small little stomach ache, indigestion, or even life-threatening conditions that require surgery.

And if all else fails, we want to know what happens to the lovely pastry when we ingest it. And it goes through this wonderful tube that we're going to talk about here. So let's get to it.

So the first concept we want to address with the digestive system is simply one long tube. So the first part of the two we want to show is the esophagus. So the beginning of the two and then this transitions into the stomach, and then the stomach becomes the small intestine. The small intestine is actually the longest portion of the whole digestive system, and the whole system can be up to 23 to 29 feet in a cadaver.

16 to 23 feet in a living person. And that's because, in a living person, the smooth muscle in the two is actually contracting and therefore shortening the two. The last part of the digestive system is the large intestine.

And this is shorter than the small intestine, as we've already addressed, but it's wider. And what's amazing to think is that this thing actually coils up in your abdominal cavity and actually fits in there and we're going to address that issue. But first, we're going to go back to the beginning and start with where we first ingest food and see what happens there.

So now that we've established that this is one long tube, now we got to go back to the beginning. And the beginning is simply ingestion we got to put something into our mouth, and ingestion and putting something into our mouth is the beginning of actually digesting food.

We do this mechanically by chewing and manipulating with the tongue. We also do it with saliva. We have a couple of salivary glands, the parotid glands, the submandibular glands, and even the sublingual glands.

A lot of you've probably experienced that aching that sometimes When you put like a sour piece of candy or food in your mouth, you can feel that aching from the salivary gland actually pushing its secretions into the mouth.

And this helps soften the food also even has some digestive enzymes to help start the digestive process. Once we've done all the chewing and salivating We then move it back to the throat. The Fancy Pant's name for the throat is called the pharynx. And anatomy.

Once we get it to the pharynx, we move to the esophagus and the esophagus essentially lies right through here.

And it's posted to the sternum and actually post here to the trachea, which is the windpipe, which I'm going to show you right now as we take a look at the guts that we had actually across the table a little bit earlier. Now we've somewhat oriented this about how it would be in the human body.

You can kind of see lower down here, we've coiled up the small intestine here.

The large intestine is this picture frame wrapping around here, a little bit higher. You can see the stomach here, but again, the beginning is this region and I just mentioned The trachea, the trachea is not part of the system.

We'll talk about it in later, so I'm going to reflect it away. And underneath you can see the Food Tube or the esophagus. Now again, each segment of the tube has a specific function we want to address these as we move through the tube and sequence.

The esophagus is pretty simple. it secretes mucus, which helps kind of lubricate itself so food can slide and glide down. It also just is simply this transport to transport food from the pharynx again, which was the throat down into the stomach.

And again, just side note, for those of you who have ever had heartburn, you can blame the esophagus, you can feel that burning sensation that has acid coming up from the stomach.

And again, you can see that relationship coming down here on the cadaver, where we have the esophagus just becoming this the stomach. The stomach, as I already mentioned, produces hydrochloric acid.

Part of it's tucked underneath the ribs, sometimes even the liver will cover up this region of the stomach as well. But one thing that's really cool about the stomach is this thing can stretch out like crazy.

Do you guys have that big, you know, binge eating during say, like Thanksgiving dinner, this thing can stretch out. And one of the things that we can show for this is another stomach over here.

Now, this stomach, you can see we've dissected away, and opened it up you can see these amazing folds called gastric rookie just literally translates to stomach folds. gastric means stomach rookie means fold.

And these things allow for stretching for that little food baby you might get on Thanksgiving dinner. So moving on from the esophagus, we go into the small intestine.

Small Intestine is broken down into three segments. Let's start with the names duodenum , jejunum, and ileum. Did you know them and lm, I had a friend who always said DJ ice. That was how he always remembered the order from duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

Now if you want to say do denim or do denim, that's fine, but we typically will say duodenum and here.

Now on the cadaveric. Here, or this segment of the gut tube that we mentioned earlier, I'm going to reflect the large intestine just away so you can see the very beginning of the small intestine, which I mentioned was the duodenum.

Now the duodenum is still going to take part in digestion, just like the stomach was digesting things by mixing things around with the acid and churning.

the duodenum has some relationships with what we call accessory digestive system organs, three of them that you've heard about the liver, the gallbladder, and the pancreas. Let's start with the liver.

Now the liver is tucked up in the right upper quadrant. This thing is the second largest organ in the human body just second to the skin. And this thing has so many functions. It's an amazing organ, but we're only going to focus on one and that Simply produces bile.

And bile is a really important substance to break down fat. You can't talk about the liver without talking about the gallbladder. The gallbladder is a little storage organ, a little storage facility, if you will, for extra bile, and that little organs tucked up under the liver or just inferior to the liver.

So say you have a nice fatty meal and you need a little extra bile, that gallbladder can squeeze some of its short bile along with the liver squeezing out some bile, and it dumps it into again, the duodenum. Before we complete this digestive story, we have to mention the pancreas. the pancreas is a really awesome organ as well.

It's involved in the endocrine system and insulin, but we're gonna focus on its exocrine function or what we call its digestive system function.

Because this thing produces all of these things called digestive enzymes or pancreatic enzymes, and these enzymes are going to break down carbs, proteins, and all the things you need to break down because we can't absorb anything.

Into the bloodstream and tell it's broken down into its little smallest components. And just real quick, the pancreas is location.

This thing is actually posted here to the stomach. Remember we mentioned the stomach is right up here, kind of covered up by the left side of the ribcage even projects into the middle.

But the pancreas kind of dives over to the left side. It kind of almost looks like it's shaped like a little bit of a governor. Sometimes people may think it looks like a tongue even but you guys can decide what you think it looks like.

Regardless, this thing is really important with the liver with the gallbladder to put all these secretions into the do a dino and the do a dino again, will then have its final digestion of these foods. And once we move from the duodenum or the duodenum, we become the jejunum.

And you can see this length the majority of the small intestine is the jejunum and the ileum.

There's not like some specific line where it says okay, this is the helium This is the genome, but the only is The last part and I'm essentially in the alien here, and I'm moving around coiling around. And why is this thing so long? That's a really important question.

The reason is, are we need as much length and surface area to absorb as many nutrients as we possibly can.

Now on this cadaver, you can't see how it's attached to the post your abdominal wall. But on this other cadaver that we're going to show here, you can see all of this yellow tissue, and in all this tissue, they're gonna see tons and tons of blood vessels.

And these blood vessels are simply for absorbing all of those nutrients out of the small intestine. So hopefully, that gives you an idea of the small intestines function.

The first part of the DNA number duodenum is going to finish digesting, digesting with the help of the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas in the genome and the aliens just gonna suck all those nutrients in.

Now coming back to this cadaver or the scut tube on the actual tray here, let's reorient you again. This was the end the only The ilium transitions into the large intestine in the first part of the large intestines called the SEACOM. So going from the ilium to seek them.

You can see the difference here, the cecum is a much larger sac or even the large intestine as a larger diameter. And the ilium and SEACOM they have a valve in between crazy name called the ileocecal valve.

This stops one way this creates one-way flow or is how I should say that it stops any food or this point feces or stool because we're no longer absorbing at this point from going back into the small intestine.

This is the transverse colon. Moving down, this is the descending colon. Now in a different cadaver, you can actually see that this would kind of squiggle out and we'd call that the sigmoid colon and that hooks up to the rectum, and eventually the anus.

|

| ☝In small intestine |

But what do all those things do as far as the A sending comb, the transverse colon, the descending colon, the large intestine, is simply this storage organ where it's going to actually store fecal matter for when we actually eventually hopefully get it to the toilet.

The other is it absorbs the last part of water and salts. So those are some important things that you want to actually keep in mind. And there's a couple of features I want to move and show you before we leave this section here. One on the SEACOM, you can't actually see what normally comes off. There's normally this little worm-like structure that comes off called an appendix. I'll be able to show you that on this cadaver, where it's this little small, worm-like structure, they actually called vermiform appendix because vermiform actually means warm like, and if I move back to the small intestine, I want to show you something that's really cool as well. If we open this up, and you can actually see these little folds right here, they call them circular folds.

Remember I asked the question, why is this thing so long, and the small intestine is so long because it's got to absorb so many nutrients. Another thing to help absorb nutrients or to increase surface area is these folds and they allow for the absorption of even more nutrients.

0 Comments

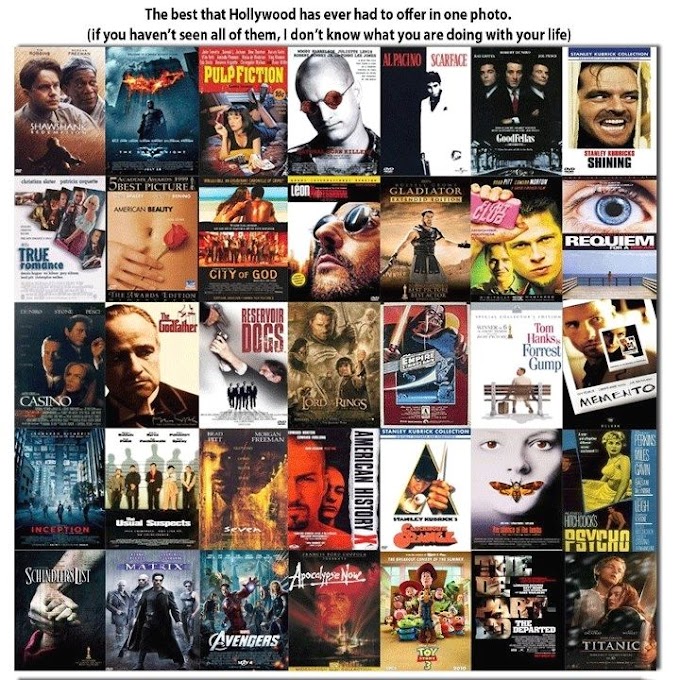

If you know the best movies.please let me know